Amidst its incredible diversity, India remains united by a shared love for Hindi cinema, affectionately known as Bollywood. Seventy-six years ago, when India gained independence, the Hindi-language film industry, one among several regional cinematic enterprises, didn’t wield the profound influence it holds today. However, its impact on the masses has captivated researchers and pop culture enthusiasts alike for years.

In a 2007 paper published in the India International Centre Quarterly, Rachel Dwyer, an esteemed author and former Professor Emerita of Indian Cultures and Cinema at SOAS, University of London, brings attention to a significant gap in research – the absence of a major ethnography on Indian cinematic audiences. The earliest attempt to record the sociological impact of the Indian film industry dates back to the Report of the Indian Cinematograph Committee (1927–1928), but it was limited to the perspectives of the “elite” class. Despite this limitation, Dwyer manages to extract relevant insights from this inquiry, revealing that even among the upper-class, there was a belief that cinema wasn’t deemed an “important cultural form,” despite some notable early contributors to the industry emerging from this social stratum.

In the 1980s, the elites distanced themselves from Bollywood due to its predominantly populist content, which primarily appealed to urban working-class males. However, the economic liberalization of the 1990s brought about the emergence of a new “middle class” with increased spending power, leading to Bollywood’s resurgence in the mainstream consciousness. Drawing from Bourdieu’s “analysis of taste in French society,” Rachel Dwyer characterizes the Indian middle classes as the “national bourgeoisie,” responsible for crafting a “hegemonic vision of Indian culture” through various government institutions such as academies, universities, and museums. This vision remained influential despite the diverse cultural landscape and social norms prevalent in the country. The cultural capital of the middle classes, their specific “taste,” came to determine the popularity of any cultural offering within the society.

Dwyer makes a clear distinction between the “old middle classes” and the “new middle classes” that have emerged in the past century. According to her, the latter group belongs to the upper end of the economic spectrum, possessing non-landed wealth, and English being one of their major languages. This affluent segment of consumers has played a crucial role in giving Hindi cinema cultural legitimacy and challenging the values upheld by the traditional middle classes.

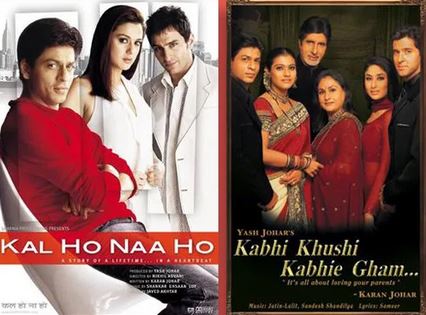

This transformation in economic status is well-reflected in the themes and subjects depicted in the movies of the respective eras. The old middle classes preferred cinema that portrayed social realities without excessive melodrama, often addressing issues related to caste, class, and gender. However, as the 1990s approached, a new wave of films emerged, focusing on romance, catchy songs, the rise of fresh stars, and more effective marketing strategies.

Dwyer draws from the insights of Ashis Nandy, an Indian political psychologist, social theorist, and critic, to illustrate that this new commercial cinema highlighted the perception that the lower middle classes had of the “haute bourgeoisie.” She suggests that the culture embraced by the new middle classes may resemble that of the lower middle classes, but it distinguishes itself by offering consumerist lifestyle opportunities akin to those of the wealthy. Simultaneously, the old middle classes may view this perception as a form of mimicry of their own culture, potentially leading them to look down upon it.

Dwyer concludes that delving into the world of Bollywood offers valuable insights into the dynamics of modern India. She focuses on the prominent cinematic themes that have emerged in recent times.

“The movies under consideration revolve around themes of social mobility, indulging in fantasies of wealth, and, notably, exploring the intertwined concepts of consumerism and romance,” she elaborates. However, Dwyer clarifies that the prevalence of middle-class values in Hindi cinema doesn’t necessarily mean that its audience solely comprises the middle class. Instead, this trend reflects a broader societal shift, where the dreams of consumerist experiences like travel, fashionable clothing, and aspirational lifestyles resonate not only with the middle class but also with the cosmopolitan and globally connected Indian youth.

In essence, Bollywood acts as a reflection of the evolving social landscape, mirroring the desires and aspirations of a diverse audience while offering an engaging glimpse into the ever-changing fabric of modern India.